Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

About Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)

The main features of this illness are obsessions and compulsions. Obsessions are certain thoughts, doubts, images or urges that occur in one’s mind. These are unwanted, repetitive by nature. Most people with OCD realize that obsessions are senseless, irrational, or excessive, but they are unable to ignore or suppress them. They would attempt to resist and control them, but would not succeed. Obsessions cause significant distress and anxiety to the sufferers and as a result cause interference in their day to day functioning.

Compulsions are repetitive acts that the person is driven to carry out in spite of knowing that they are meaningless, unnecessary or excessive. Compulsions are usually in response to obsessions. For example, a person with an obsessive fear of contamination washes hands repeatedly in order to ensure that his or her hands are clean. The person attempts to resist repeated hand-washing, but gives in to the urge so as to relieve himself or herself of the anxiety or discomfort. Persons with OCD often perform certain acts repeatedly to avoid some dreaded event or to prevent or undo some harm to themselves or others. For instance, touching the floor even number of times to prevent an accident that one fears might occur to family members. They are aware most of the time that the activity is not connected in a logical or realistic way with what was intended to be achieved, or that it may be clearly excessive (as in the case of hand-washing compulsions), but cannot control them as they reduce anxiety, at least transiently. Some compulsions can be in the form of elaborate ‘rituals’. Rituals are a particular sequence of actions, which the person is compelled to carry out. On either changing the sequence or missing out one of the actions, anxiety increases driving the person to repeat the set of actions all over again. This would lead to spending considerable time in carrying out even a simple routine activity such as washing hands.

Epidemiology

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a common mental illness. Earlier it was considered as a rare illness, but studies have now shown that 2-3% of the population have OCD at some point in their life. Though OCD is a common illness, many who suffer from this illness do not seek treatment. In the west, less than 50% have contacted psychiatrist for treatment and in India, it is only to be expected that even fewer numbers would have sought treatment for this illness. It occurs in all age groups. Sixty five percent develop their illness prior to age 25 years, some as early as 5 years. Less than 15% develop their illness after age 35 years. It is equally prevalent in both sexes, but more common in boys than in girls if the onset of illness is in childhood and adolescence.

Some common obsessions:

- Fear of getting dirty, contaminated or infected by persons or things in the environment.

- Blasphemous thoughts.

- Thoughts of harming or killing others or oneself.

- Recurring thoughts or images of sexual nature.

- Fear of blurting out obscenities.

- Fear of developing a serious life-threatening illness.

- Preoccupation to have objects arranged in a certain order or position.

Some common compulsions:

- Repeated hand-washing, taking unusually long time to bathe, or cleaning items in the house.

- Ordering or rearranging things in a certain manner.

- Checking locks, electrical outlets, gas knobs, light switches etc. repeatedly.

- Repeatedly putting clothes on, then taking them off.

- Counting over and over to a certain number.

- Touching certain objects in a specific way.

- Repeating certain actions, such as going through a doorway.

- Constantly seeking approval (especially children).

Fear of contamination and washing and cleaning compulsions:

It is the most common obsession. The person feels contaminated and dirty even on carrying out routine chores such as handling door knobs, picking up fallen objects, using money handled by others or just pass by a garbage can. These fears and rituals are of extreme nature – the washing may consume many hours and may leave the hands raw. Also, they may spend hours keeping the house clean, or cleaning the bathroom repeatedly before taking bath.

There are some who fear that the dirt and germs brought in by themselves or others would spread and cause harm to others. Hence, they would avoid touching others till they have a bath or clean up the whole house after someone visits. The washing could sometime become highly ritualized such as scrubbing the hands in one particular way or taking bath in a particular order. When not performed as per the ritual they may become extremely distressed and anxious and repeat the act all over again till they are satisfied or get tired.

Doubting and checking:

Persons with these obsessions have repeated doubts that something bad will happen because they have failed to check something thoroughly or completely. Their need to check repeatedly is driven by the possibility that something terrible will happen even though they recognize that the possibility is an extremely remote one. For example, the doubt that the gas knob is not turned off properly and as a result gas will leak and result in a fire accident. Common examples are, repeated checking of door locks, gas knobs, and electric appliances. Other common examples include, counting currency notes repeatedly, and going over a file or homework assignment (in case of children) repeatedly to check for any possible errors. However, even after spending considerable time in checking they are rarely satisfied. Sometimes, they may seek reassurance from others to ensure that they have not committed any mistake that may prove to be dangerous. For a casual observer, they may appear very slow and inefficient, particularly at work. Children with checking compulsions are often seen as poor learners at school and may fall behind in studies. If one asks these patients, “When are you satisfied that the door is really locked?” Many would say that they are never completely satisfied. Some patients employ certain strategies to reduce the amount of time spent in checking. The most common is to limit the number of checks by counting. These patients often end up developing counting rituals, such as developing a system of good or bad numbers.

Need for symmetry and ordering / arranging:

Persons with these obsessions are usually seen as those who like to keep everything neat and tidy. But the need to be tidy would be a major preoccupation and take priority over carrying out other routine activities. They would want to keep objects in a particular order and get very much upset if they are out of place. They would not rest till they put back things in an order, as they would otherwise experience a sense of discontent or tension, than fear or anxiety. They may spend hours arranging the table for a meal or making a bed till satisfied that everything is in the right place.

Sexual and aggressive obsessions:

People with these obsessions have repeated thoughts or images of sexual or aggressive nature. For example, sexual obsessions could be in the form of intrusive sexual images of family members and gods and goddesses. Aggressive obsessions are usually about urges to harm loved ones, usually family members. Persons suffering from sexual and aggressive obsessions suffer from intense guilt and anxiety. Their constant fear is that they might actually act out on their obsessions. As a result, they tend to seek reassurance from others just to make sure that they are not really capable of doing what they are worried about.

Counting and repeating compulsions:

Children with OCD may spend hours unnecessarily counting certain things. They may count the number of people on the street, the bars on a window, the tiles on the floor and repeat it. Some may have to count up to a certain number before initiating or completing a task. They may have to count the number of steps taken to cross a particular distance. Persons with repeating compulsions would repeat a certain task several times, such as, circle a chair or shuffle certain number of times before sitting in the chair.

Ruminations:

Persons with these obsessions spend a great deal of time thinking about issues that they consider irrelevant but would be unable to stop them. Ruminations generally involve prolonged inconclusive thinking about unanswerable questions or endless doubting over ordinary matters. They may also involve the activities of the day or conversations that they have had during the day.

Hoarding:

It is not uncommon for people to keep old or used objects such as clothes, containers and paper for some future use. But those suffering from OCD may carry this to an extreme. Family members and friends often complain that the person can no longer function because of the sheer accumulation of unwanted material in their room and office. These patients are compelled to check their possessions over and over to make certain nothing is missing. They would be extremely anxious if told to discard some used objects.

What are not obsessions?

The common usage of the word obsession as in, “he is obsessed with music” is not obsession as used in the context of OCD. Here the person indulges in the activity with complete will, has control over them and derives pleasure out of the activity.

When one is fired from a job or loses someone close to them, it is natural to brood over the event. However, these thoughts are not considered as senseless or irrational, though they may cause some discomfort. Similarly, a person appearing for an examination may feel anxious and worry about the results, which could occupy considerable amount of his time. These thoughts, though unwelcome, are under his control and not experienced as senseless. The above experiences are obviously not obsessions.The common usage of the word obsession as in, “he is obsessed with music” is not obsession as used in the context of OCD. Here the person indulges in the activity with complete will, has control over them and derives pleasure out of the activity.

The exact cause of OCD is still unknown. However, there are many theories of causation of OCD. These are broadly classified into biological and psychological theories.

Biological theories:

At this stage, it is fairly clear that OCD has a biological basis and is caused by certain biochemical changes occurring in the brain. These changes involve neurotransmitters, which are chemical substances that aid in the transfer of messages across nerve cells. A neurotransmitter called serotonin is said to be deficient in the brains of individuals suffering from OCD. The most compelling evidence implicating involvement of serotonin in OCD is the efficacy of drugs belonging to the class of serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SRIs). These drugs increase the concentration of serotonin in the brain and thus ameliorate the symptoms of OCD.

Further evidence that OCD is a disorder of biological origin comes from its association with some neurological disorders. Individuals with encephalitis, tic disorders and chorea are more likely to develop OCD. Moreover, brain imaging studies using Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) and Positron Emission Tomography (PET) have show abnormalities in some regions of the brain, such as, the frontal lobes, cingulum and basal ganglia. A circuit connecting these brain regions is thought to be dysfunctional in individuals suffering from OCD.

It is now believed that OCD is a heritable disorder in some patients. About 3-7% of first-degree relatives (parents, siblings and children) of individuals suffering from OCD have similar illness. OCD is also genetically related to a neurological disorder called ‘Tourette disorder’. The relatives of individuals suffering from OCD have, not only a higher propensity to develop OCD, but also Tourette disorder. Similarly, the relatives of individuals suffering from Tourette disorder have a higher propensity to develop OCD. It should, however, be noted that OCD is a heritable disorder in only a minority of individuals. Most individuals suffering from OCD do not have any relatives suffering from the same illness.

Role of stress:

Stress of any kind, by itself, does not cause OCD, but can precipitate the onset of OCD in vulnerable individuals. But, stress is well known to worsen pre-existing symptoms. The common precipitating stressful life events include separation from loved ones, major life changes such as loss of a job, problems at work, pregnancy, childbirth, and abortion.

Role of personality:

There are some individuals who are very perfectionistic, rigid and meticulous in what they do. They are excessively preoccupied with order, precision, rules and organization. These individuals are said to suffer from obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, but not from OCD. It was earlier believed that this type of personality predisposes one to develop OCD. However, it is now clear that the presence of this personality disorder need not predispose an individual to develop OCD. In fact, most patients with OCD do not have obsessive-compulsive personality. On the contrary, individuals with low self-esteem, who are easily hurt by criticism, and who display anxiety in interacting with others and in participating in social situations such as parties and marriages are comparatively more likely to have OCD.

Psychological theories:

For many years psychiatrists believed that OCD developed in individuals who had been brought up by rigid and strict parents. It is now clear that such is not the case and that psychological conflicts and deep-rooted problems of early childhood do not cause OCD.

According to the learning theory, obsessions and compulsions develop in two stages. In the first stage, a neutral stimulus such as a thought or an image becomes associated with fear because it is paired with an event that by its nature provokes discomfort or anxiety. Through this association, thoughts and images become capable of producing distress. In stage two, the patient develops avoidance responses such as avoiding using knives because of fear of hurting others, because avoidance reduces anxiety. However because many of the fear-provoking situations cannot be avoided, compulsions develop to prevent or reduce discomfort. Because avoidance and compulsions reduce anxiety to some extent, they tend to persist thus establishing a vicious cycle difficult to break. Evidence supporting the acquisition of obsessions is inadequate, because most patients do not recall any specific aversive events associated with symptom onset. But there is enough evidence to suggest that obsessions are maintained because of avoidance and compulsions.

OCD is a common mental disorder, and is often disabling. In addition, a majority of patients with OCD are at high risk of having one or more co-morbid (co-existing) psychiatric illness. Anxiety disorders and depression are the common co-morbid conditions reported in most studies of OCD. The most common concurrent psychiatric disorders were major depression (30-55%), social phobia (11-23%), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) (18-20%), simple phobia (7-21%), panic disorder (6-12%), eating disorder (8-15%), tic disorders (5-8%) and Tourette’s syndrome (5%).

In addition to anxiety and depressive disorders, a fascinating group of conditions called obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders are also found to be highly co-morbid with OCD. These include Tourette’s syndrome and other tic disorders, Hypochondriasis, body dysmorphic disorder, trichotillomania, and eating disorders. These disorders are considered to be related to OCD because of similarity in clinical picture (morbid preoccupations and compulsive behaviour), high rate of comorbidity, and somewhat similar treatment response. It is extremely important to identify and treat coexisting psychiatric conditions because untreated co-morbid conditions could contribute to poor treatment response and prognosis. Studying comorbidity also helps in understanding the possible etiological relationship between the disorders.

MOOD DISORDERS

Major depressive disorder

Depression is the most common co-morbid disorder in OCD. With the available studies it can be concluded that out of every four OCD patients one will be suffering from depression at any given point of time. It is characterized by depressed mood, loss of interest or pleasure in daily activities, and fatigue or loss of energy. Other typical symptoms of major depression include decreased psychomotor activity, decreased sleep, decreased libido, decreased appetite, ideas of guilt/sin, feelings of helplessness/hopelessness/worthlessness and death wishes/ suicidal ideas or attempts. Most patients with OCD view their depression as secondary to the hopelessness associated with their obsessive-compulsive symptoms. It is of great clinical relevance to identify and treat depression because untreated depression interferes significantly with treatment particularly with behaviour therapy.

Bipolar disorder

It is a disorder characterized by episodes of mania and depression. A manic episode is characterized by euphoria/elation, expansive or irritable mood, inflated self-esteem or grandiosity, increased activity, decreased need for sleep, overtalkativity, subjective experience that thoughts are racing, distractibility, increased libido, and excessive involvement in pleasurable activities that have a high potential for painful consequences (unrestrained buying sprees, sexual indiscretions, or unrealistic business investments). There is limited data on the comorbidity of OCD and bipolar disorder but the available data suggests that nearly 15% of OCD patients have bipolar disorder, mainly hypomania that is often precipitated by use of antidepressants. It has also been found that 21% of the bipolar patients in the ECA sample had OCD. A co-morbid diagnosis of bipolar disorder in OCD has important clinical implication in that the mood stabilization may have to be achieved before prescribing antidepressant medications to treat OCD. Antidepressant medications are known to precipitate mania.

ANXIETY DISORDERS

Comorbidity of OCD with anxiety disorders is quite high, ranging from 25-60%. Conversely, studies in primary anxiety disorders have showed comorbid OCD in 11-14% of the patients.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

GAD is characterized by chronic, uncontrollable excessive anxiety and worry (apprehensive expectation) about a number of events or activities such as work, finances, job responsibilities, safety of family members or even minor matters such as household chores, car repairs, or being late to office. The person finds it difficult to control the worry and also report of associated symptoms like restlessness or feeling keyed up or on edge, being easily fatigued, difficulty in concentrating, irritability, muscle tension and sleep disturbance. There may be associated symptoms of anxiety such as trembling, twitching, cold and clammy hands, dry mouth, sweating, palpitations, nausea, increased frequency of micturition and defecation, and an exaggerated startle response. The excessive worry along with physical symptoms causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. The comorbidity of OCD with GAD is of interest because of the seeming similarity between obsessions in OCD and worries in GAD. Obsessions are not simply excessive worries about everyday or real life problems, but rather are unwanted, irrational and unreasonable intrusions. In addition, most obsessions are accompanied by compulsions that reduce the anxiety.

Panic Disorder

In order to fully describe panic disorder, it is first necessary to define panic attacks. A panic attack is discrete period of intense fear or discomfort, associated with prominent somatic or cognitive symptoms such as sweating, trembling or shaking, shortness of breath, a sensation of choking, chest pain, palpitations, nausea or abdominal discomfort, dizziness or feeling faint, fear of losing control or going crazy, fear of dying, numbness/tingling sensation, feelings of being detached from reality, and feelings of being detached from oneself. The primary feature of panic disorder is a history of panic attacks, as defined above, followed by persistent anticipatory anxiety about having further panic attacks, excessive concern about the implications and/or consequences of the panic attacks (e.g., losing control, having a heart attack, going crazy) and substantial modification of daily activities in an effort to avoid further panic attacks. They may develop agoraphobia. Basically, they avoid any situation they fear would make them feel helpless if a panic attack occurs. These include fears of being outside the home alone, being in a crowd or standing in a line, being on a bridge and traveling in a bus, train or automobile. Some patients become house bound because of fear of traveling alone or going out alone.

Phobias

Phobias are characterized by recurrent, excessive, irrational fear of a specific object or situation. Exposure to the feared object or situation results in an immediate and intense anxiety, sometimes to the extent of having a panic attack. Despite recognizing that the anxiety is excessive, individuals with a phobia will go to great lengths to avoid exposure to the feared object or situation in order to prevent the emotional distress it causes. The anxiety and associated avoidance behaviours can cause significant emotional distress and may considerably interfere with daily functioning. Some examples of phobias include fears of flying, heights, water, elevators, insects, blood, darkness, tunnels, bridges, enclosed spaces, and dental procedures.

Social Anxiety Disorder

Social anxiety disorder also known as social phobia is an intense, recurrent fear of social or performance situations. Individuals with social anxiety are afraid that they may behave in an embarrassing manner in front of others and that they may be ridiculed or negatively evaluated. Because of the fear of criticism and negative evaluation, individuals with social phobia avoid social interactions or endure with significant anxiety. Exposure to the feared social situation sometimes results in a panic attack. The anxiety and avoidance behaviours cause significant emotional distress, and may considerably interfere with daily functioning particularly in the area of interpersonal relationships. Some examples of feared social situations include public speaking, interacting with superiors and with people who are not very well known to them, attending personal interviews, speaking to opposite sex, eating and writing in public, using public restrooms/toilets, and participation in social events such as parties and wedding ceremonies.

THE OBSESSIVE-COMPULSIVE SPECTRUM DISORDERS

There are various conditions that have shared features with OCD. These disorders are frequently described as obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders (OCSD) (Allen & Hollander, 2000; Jaisoorya et al., 2003). They include hypochondriasis, body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), anorexia nervosa, Tourette syndrome (TS), trichotillomania, binge eating, compulsive buying, kleptomania, pathological gambling, and sexual compulsions. The shared features include similarities in symptom profile and treatment response and possibly somewhat similar pathophysiology. The OCSDs are characterized by pathological preoccupations that are similar to obsessions and either compulsive or impulsive behaviours. For example, in hypochondriasis, BDD and anorexia nervosa there is morbid preoccupation with fear of having a disease, imagined ugliness or defects in appearance, and with thinness respectively. Individuals with OCD may repeatedly wash their hands in an attempt to reduce the anxiety associated with fear of contamination. In hypochondriasis, there is compulsive doctor shopping to investigate a disease and in BDD, they check themselves compulsively in front of mirror exploring their imagined ugliness or defects in appearance. In addition to similarities in clinical picture, both OCD and OCSDs respond well to a class of antidepressants called serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

Body Dysmorphic Disorder

BDD is an obsessive preoccupation with a perceived defect in one’s physical appearance. The BDD obsessions may manifest as excessive, disproportionate concerns about a minor flaw, or as recurrent, anxiety-provoking thoughts about an entirely imagined defect. The obsessions are most frequently focused on the head and face (misshapen nose, protruding jaw), but may involve any body part (genitals, breasts). BDD goes beyond normal concern with one’s appearance, and may significantly impair academic and professional functioning, as well as interpersonal relationships. The individuals often fear they will be rejected or ridiculed by others because of their ugliness or defects in appearance and have a tendency to avoid social situations. In extreme cases, an individual may completely shun any contact with people in an effort to avoid having the defect being observed by others. In order to alleviate their anxiety, patients may partake in compulsive behaviours such as repetitive mirror-checking, excessive grooming, touching and/or measuring of a minor or imagined defect/flaw in front of mirror. A relatively high comorbidity exists between BDD and OCD. Nearly 12–24% of the patients with OCD have co-morbid BDD. Similarly about on third of BDD patients have OCD. The symptoms of the two disorders are similar; they are characterized by obsessive preoccupations and checking. However, if the focus of the obsession is only about appearance, a diagnosis of BDD is preferred over OCD. The characteristic difference between these disorders is insight. Insight of patients with BDD seems to be significantly more impaired than that of patients with OCD. This lack of insight can lead to a delay in seeking psychiatric treatment. Instead, because they consider their perceived defects to be real, many people with BDD present to specialists such as plastic surgeons, dermatologists, or dentists.

Hypochondriasis

The fear or belief that one has a severe illness characterizes hypochondriasis. This fear is based on an individual’s misinterpretation of signs and symptoms, and results in multiple doctor visits and medical tests. Patients tend to indulge in repetitive checking of the body for symptoms of an alleged medical condition, and Internet searching for information about illnesses and their symptoms (cyberchondria). This behaviour persists despite medical reassurance that the individual does not have a disease or illness. Recent studies have shown that hypochondriasis and OCD are common co-morbid conditions. Both the conditions have similar clinical picture. OCD patients with somatic or illness obsessions are often indistinguishable from patients with hypochondriasis. As in OCD, hypochondriac fears are intrusive, distressing and not easily responsive to reassurance. Patients with hypochondriasis also indulge in compulsive checking of one’s body or with others. However, there are some differences, which help in differentiating OCD from hypochondriasis. In OCD there is a fear of getting an illness whereas in hypochondriasis there is a fear of having an illness. Insight is fairly well preserved in OCD and patients often admit their fears are unrealistic but in hypochondriasis there is a high degree of conviction that they have a disease. An exception to this difference is the OCD patients with poor insight. Lastly, hypochondriac fears are usually secondary to somatic sensations.

Trichotillomania

Trichotillomania is the recurrent, compulsive pulling out of one’s own hair, resulting in observable hair loss. The most common hair pulling sites are the scalp, eyebrows, and eyelashes. An individual may use his or her fingernails, as well as tweezers, pins or other mechanical devices. Usually, but not always, hair pulling is preceded by a high level of tension and a strong urge. Likewise, hair pulling is usually, but not always, followed by a sensation of relief or pleasure. Hair pulling is usually done alone, often while watching TV, reading, talking on the phone, driving or while grooming in the bathroom. Sometimes hair pulling is done as a conscious behaviour, but it is frequently done as an unconscious habit. Trichotillomania often coexists with depression, OCD, skin picking, BDD and tic disorders.

Tic disorders

In the recent past, there has considerable interest in the relationship between tic disorders, particularly the Gilles de la Tourette syndrome (GDLT) and OCD. The group of tic disorders includes transient and chronic tic disorders and the GDLT. In the transient tic disorder, tics usually do not persist for more than 12 months whereas in chronic tic disorders either motor or vocal tics persist for longer periods. The GDLT is a classic syndrome consisting of multiple chronic motor tics, and one or more vocal tics and coprolalia with onset during childhood or adolescence. Tics are defined as rapid, repetitive muscle contractions or sounds that usually are experienced as outside volitional control and which often resemble aspects of normal movement or behaviour. Tics can be elicited by stimuli or preceded by an urge or sensation. They are usually beyond attempts at suppression.

Examples of motor tics include eye blinking, head jerks, shoulder jerks, finger and hand movements and stomach jerks. Vocal tics include throat clearing, coughing, grunting sounds, repeating certain words and sentences, repeating others’ speech, and coprolalia (repeating obscene or socially unacceptable words). Some complex tics include facial gestures, grooming behaviours, jumping, touching, stamping and hopping. Patients with GDLT have a high rate (30-40%) of co-morbid OCD and obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Conversely nearly one fifth of OCD patients have a lifetime history of multiple tics and 5% to 10 % have GDLT. Family studies of GDLT and OCD clearly show a relationship between the two disorders. Relatives of GDLT patients report a high rate of OCD and relatives of OCD patients report a high rate of tic disorders and GDLT. In an Indian study, tic disorders were present in 18% of OCD patients but the rate of GDLT was only 3% (Jaisoorya et al., 2003). The subgroup of OCD plus tic disorder patients have an earlier age-at-onset of OCD with high family loading for GDLT and OCD (Pauls et al., 1995). In a study of children and adolescents with OCD, 56% had tics and 14% has GDLT (Leonard et al., 1992). However, in an Indian study of children and adolescents with OCD, tic disorders were present in 17% of the subjects and GDLT in only 7% (Reddy et al., 2003). It appears that tic disorders are not uncommon in Indian OCD patients but for some unknown reasons, GDLT is a rare co-morbid diagnosis

Eating disorders

In anorexia nervosa, patients restrict their food intake to the point of being underweight and experience distressing concerns about their shape and weight, particularly intense fear of weight gain or being at even though grossly underweight for their age and height. They deny the seriousness of low body weight and further feel driven to exercise for hours a day and use other extreme measures such as laxatives, diuretics, or self-induced vomiting in their attempts to lose weight or maintain low body weight. In essence, they have an obsessive fear of being fat and are characterized by a relentless pursuit of being thin. In bulimia nervosa, patients have episodes of binge eating in which they consume a large amount of food in a discrete period of time, often with the feeling of being out of control.

PERSONALITY DISORDERS

Nearly a half of patients with OCD also have at least one diagnosable personality disorder. The most frequently diagnosed personality disorders among patients with OCD are avoidant, dependent, histrionic, passive-aggressive and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders. Some researchers report no specific association between obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (OCPD) and OCD but few recent studies have reported high rates of OCPD in OCD. Less frequently diagnosed were paranoid, borderline and schizotypal personality disorders, which are found to be associated with poor outcome. The issue of whether PD is the primary or secondary disorder is debatable. Early onset OCD imparts its signature as traits on the development of personality of an OCD patient. Recent literature shows that the number of personality disorder diagnoses, and scores on personality disorder measures, declined in half of the OCD patients following successful treatment. Now it becomes all the more important to recognize it and treat it before it becomes enduring personality trait.

CONCLUSION

Co-morbid psychiatric disorders are common in OCD. Depressive and anxiety disorders are the most common co-morbid conditions in OCD. Recently, there has been considerable interest in co-morbid OCSDs. The putative OCSDs that are strongly related to OCD include tic disorders, hypochondriasis, BDD, eating disorders and trichotillomania. Relationship between schizophrenia, bipolar disorders and OCD requires further exploration.

While obsessions and compulsions are seen primarily in OCD, they may also be found in other psychiatric conditions. These conditions share certain characteristics with OCD such as clinical features, course of illness, causative factors and response to treatment. They include

- Body dysmorphic disorder

- Trichotillomania

- ourette syndrome

- Eating disorders

- Pathological gambling

- Compulsive buying among other disorders

These OC spectrum disorders may occur independently in an individual or may be present along with OCD.

In Body Dysmorphic Disorder there is excessive preoccupation with an imagined defect in one’s physical appearance. For e.g., A “crooked” nose, “thinning” hair or “scarred” skin. If a slight abnormality is present, the concern shown is markedly excessive. These individuals tend to spend a lot of time in front of the mirror checking the imagined defects repeatedly, apply make-up to hide the imagined flaw and make repeated visits to doctors especially plastic surgeons for repair of their defect.

Trichotillomania or compulsive hair pulling consists of repetitive pulling out of one’s own hair. A sense of tension is experienced just before hair pulling and pleasure or relief occurs during the behaviour. Any body hair may be targeted, though most often scalp hair is involved.

In Tourette syndrome patients have involuntary movements of various body parts such as head and shoulder jerking, eye-blinking etc. In addition, they tend to make certain sounds (e.g., Throat clearing, screaming, hiccups) and utter obscenities involuntarily.

Eating, shopping and sometimes even gambling are considered normal and routine experiences for most people. However, when these behaviours become excessive, distressing and difficult to control, they are called eating disorders, compulsive buying and pathological gambling respectively.

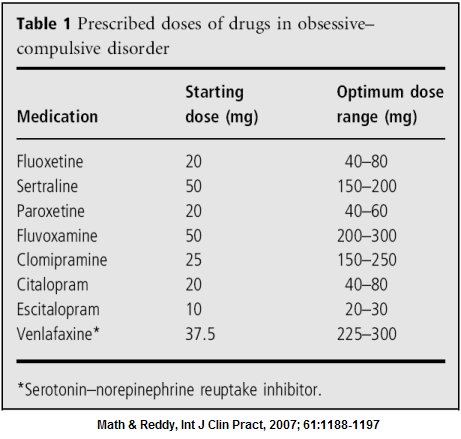

Till the 1980s there were no effective drugs which were available for the treatment of OCD. However, since then a class of drugs has been found to be effective in the treatment of this disorder, and newer drugs belonging to this class are also being found effective. This group of drugs are the Serotonin re-uptake Inhibitors. There are various chemicals or neurotransmitters in the brain, and serotonin is one of them. These drugs act to increase the amount of serotonin available for the nervous cells in the brain. This corresponds to the known serotonergic hypothesis for the etiology of OCD (See the section on Causes of OCD). Drugs acting on other neurotransmitter sites, such as dopamine (anti-psychotics), noradrenaline (other anti-depressants) or GABA receptor complex (sedative hypnotic) are not effective. The oldest member of this group is clomipramine. More recent additions to this group, and more selective in their mechanism of action, include fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, sertraline, paroxetine, citalopram and escitalopram.

These drugs also belong to the larger category of drugs called anti-depressants. There has for a long time been some controversy whether these drugs treat depression or OCD. However, the consensus opinion at this point of time is that although they have potent actions on depression, they also have independent anti-obsessional properties. So whether you are depressed or not, and in spite of the broader classification of these drugs, these drugs will work for you, if you have OCD. These medications are also useful in treating a number of disorders that can co-occur with OCD. These include hypochondriasis, social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and premature ejaculation.

Choice of a specific drug is arbitrary, and more often dictated by the side effect profile and the prescriber’s comfort, than by evidence that any one of the Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors are more effective than the other. There is some evidence that clomipramine may be slightly more effective than other medications; however, because of its higher likelihood of side effects, it is usually used when at least one other medication has not been effective.

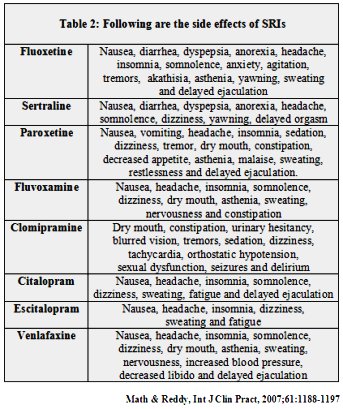

The table below summarizes the drugs commonly used in OCD and the doses usually prescribed. Apart from clomipramine, most of the other medications have very similar side-effects.

Table 1 Prescribed doses of drugs in obsessive-compulsive disorder

Most of these medications are given in the evening as a single dose, after dinner. The exceptions are fluoxetine and sertraline, which is given in the morning as it may cause disturbed sleep, and fluvoxamine which is usually given twice daily. Taking medications with food may reduce some of the side effects, such as nausea or diarrhoea. Some patients taking these medications experience an initial worsening of anxiety or restlessness for the first few days or weeks of treatment. Most of the side effects mentioned in the table 2 are usually mild and settle down by themselves over a few weeks; if they are persistent and troubling, please consult your doctor.

Table 2 Following are the side-effects of SRIs

Clomipramine is usually reserved for patients who are not responding to one of more of the other medications. It must be used with caution in patients with certain medical problems, such as glaucoma, prostatic enlargement, epilepsy or cardiac disorders; in such cases, your doctor will probably prescribe clomipramine only after consulting a specialist in the concerned disorder. Seizures are very uncommon except at doses of 250 mg/day.

There is no clear-cut guideline as to how long drug therapy needs to be continued for. There are reports that these drugs are effective for periods as long as 1-2 years, but when one should stop treatment is not clear. In some small studies, relapse rates varied from 60-80% after drug therapy was stopped. These are definitely high. However there are no studies giving us information on combination of drug and behaviour therapy, and discontinuation. If you remain relatively well, it is likely that your treating psychiatrist will try and gradually stop your medicines after 1-2 years, and see if symptoms reappear. If you remain symptom free, then you do not need to take drugs. Otherwise the drugs will have to be reinstated. It is unfortunate that OCD is a chronic illness, and that often the treatment lasts for a long period of time. It can be compared to diabetes or high blood pressure in this medical model.

However attempts can be made to decrease your dosage after you have shown adequate improvement. This will be done in small steps every 1-3 months, to about 60% of the dose to which you had shown response, 6 months to a year after initiating therapy.

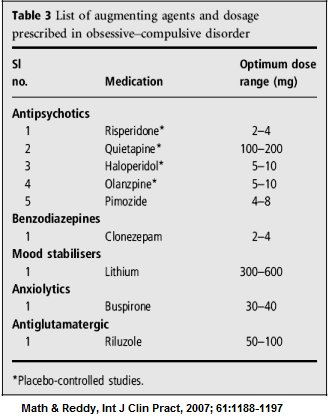

Unfortunately, there is a significant percentage of patients (about 40%) who do not respond to single drug therapy. If behaviour therapy is also used as an adjunct, this figure comes down to about 20-30%. For this group of patients we have the option of adding other drugs to your ongoing treatment. These medications are known as “augmenting agents”. The table below describes some of the common augmenting agents. Your treating psychiatrist will give you additional information in this regard, once the need for such treatment arises. Other medications, not mentioned in the table below, but are being now commonly used as augmenting agents include Aripiprazole, Amisulpiride, Memantine, N-Acetyl Cysteine, Ondansetron & Granisetron. Sometimes other medications will be recommended; this will be done only in exceptional circumstances and after explanation by your doctor.

Table 3 List of augmenting agents and dosage prescribed in obsessive-compulsive disorder

In spite of our best efforts at vigorously treating OCD, a small percentage of patients do not improve. This subset of patients, who do not respond to adequate trials of medications and cognitive behaviour therapy, are termed to be ‘treatment refractory’. Options for treatment refractory OCD include psychosurgery or Psychosurgery has been advocated as the last treatment of choice in the refractory OCD patient. However, psychosurgery gives improvement rates of only 30-50%, is associated with potentially serious side-effects, and can be tried only as a “last resort” when both medicines and behaviour therapy have failed. There have been several advancements in the technique of psychosurgery for OCD in the last few decades. The two most widely used procedures are anterior capsulotomy and anterior cingulotomy. They are done by gamma-knife radio-surgery, which involves producing a small lesion in very specific areas of the brain non-invasively using carefully focused gamma radiation. The procedure is also not widely available, and is used only by experts in the field.

Various brain-stimulation techniques have been tried in OCD in the last decade. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) has shown to be of no benefit for the treatment of OCD. Research on newer techniques such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) have shown mixed results, and more research in this area is under way.

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is another very recently emerging surgical option for the treatment of refractory OCD. In this approach, a pulse generator is implanted under the skin in the chest wall, akin to a pacemaker, which is connected to electrodes which are very carefully inserted through the skull to stimulate specific areas of the brain. There have been a few studies from certain specialized centres in the world that have shown promising results. The procedure is reversible, that is, the device can be switched on or off. However, there is a high risk of damage to other areas of the brain during implantation, and would require intense post-operative care and frequent follow-up visits for programming the device, checking the battery status, etc.

What is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) ?

Cognitive Behavioral therapy comprises of a variety of techniques used to modify or replace maladaptive thoughts, emotions and behaviors with more adaptive forms of the same. Obsessions and compulsions seen in OCD are examples of maladaptive behaviors as they cause significant distress and interfere with normal functioning of an individual. Behavior therapy helps to remove obsessions and compulsions and thereby ameliorate the distress.

In treating OCD several CBT techniques are used. Of them, “Exposure and Response Prevention”, is the most effective and widely used technique. It is effective in 60-70% of patients suffering from OCD.

The rationale behind Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for OCD:

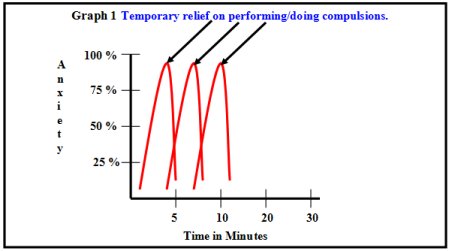

We know that most patients suffer from both obsessions and compulsions. Compulsions are performed to reduce the anxiety or discomfort associated with obsessions. Because the compulsions succeed, even if momentarily, in reducing anxiety, the compulsions are reinforced and are more likely to occur again in response to obsessions or certain situations which trigger obsessions. In the due course of time, for most patients, the compulsions which were originally employed to reduce the distress, themselves become a source of great discomfort. To put it simply, the obsessions lead to compulsions, and because the compulsions reduce the anxiety due to obsessions, they tend to persist establishing a vicious cycle difficult to break.

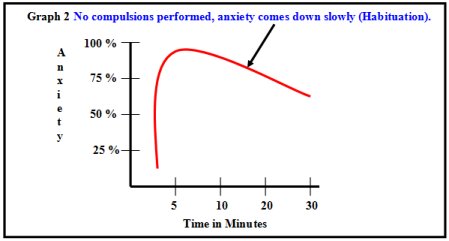

The “Exposure and Response prevention” technique based on the principle of “habituation” of emotions breaks this vicious cycle. What then is habituation? It is based on a simple principle that irrational fears and behavior disappear upon repeated exposure to the sources of fear and anxiety. By repeated and prolonged exposure, the individual gets habituated or used to the anxiety or discomfort to the point where the sources of fear lose their ability to provoke any anxiety, fear or discomfort. However, patients with OCD tend to handle their fear and anxiety by indulging in compulsions and active avoidance of all those situations that could trigger obsessions. On the contrary, in behavior therapy, patient is encouraged to gradually expose oneself to the anxiety-provoking situations and get habituated to the discomfort. And also, the patient is encouraged to not avoid any situations and indulge in compulsions. By preventing oneself from performing compulsions. The anxiety associated with obsession gradually dies on its own. Once the patient get used to anxiety the obsessions and compulsions also gradually disappear.

Take for example, the patient who washes hands repeatedly whenever he touches door-knobs because of the fear of contamination In behavior therapy, the patient is encouraged to tough the door-knobs but prevented from hand washing. By doing so, the patient’s anxiety shoots up but gradually comes down on its own and the patient gets used to it. On the other hand, if the patient indulges in hand washing. Anxiety drops down quickly not allowing the person to get used to it. Result, his or her fear of contamination persists and the person has to indulge in time consuming and distressing compulsions to get rid of the fear of contamination (Graph – 1).

Graph 1 Temporary relief on performing/doing compulsions

If patient perform compulsions in response to anxiety related to obsession, than he gets temporary relief. But he has to perform compulsions when ever he gets these obsessions. The only way then to break this vicious cycle is to expose but not to wash hands. By such repeated exposures, the fear of contamination gradually disappears and hence the compulsion of hand-washing also(Graph – 2).

Graph 2 Habituation graph when no compulsions are performed

If a patient doesn’t perform any compulsion in response to obsession, then anxiety comes down slowly on its own which is called habituation. Then he doesn’t require performing compulsions whenever he gets these obsessions.

Analysis of the symptoms and implementation of treatment:

1. The first step is careful and detailed documentation of all the obsessions and compulsions.

2. Having done that, all the objects and situations that provokes obsessions and compulsions. Are identified and arranged in a hierarchy of situations from the least anxiety provoking to the most anxiety provoking ones.

3. The information is also obtained about all the objects and situations that the patient avoids to control rituals. For example, a patient may avoid public toilet to prevent having to extensively wash his or her body or clothes. Like objects and situations, certain thoughts and images can also trigger anxiety, panic or discomfort and lead to ritualistic behaviors. For example, blasphemous thoughts may get triggered in a person upon seeing photographs of gods and goddess and visiting temples. To escape from the anxiety the person may end up avoiding temples and praying.

4. In some patients the obsessions and compulsions occur only in home It is very vital to have this information as the treatment has to be accordingly entirely home based, and with full cooperation of other family members.

5. Finally, in some patients, rituals are reinforced by family members ‘co-operation is sought to implement the treatment.

It is important to understand at the outset, that the treatment causes discomfort and that one should be prepared to go through some discomfort to obtain relief ultimately. The speed of habituation of emotional responses varies from person to person. Some may require lesser time (e.g. 30 min) of exposure while others may require repeated long exposures (1-2 hours) before any diminution of the anxiety occurs. Usually the compulsions and rituals are the first to respond and the obsessions take longer to “wear out”. Most show response between 10-12 hours of exposure and response prevention. For a successful outcome, motivation to get well and withstand the discomfort in initial sessions is vital.

REMEMBER THESE STEPS IN ERP

(Adapted and modified from Schwartz et al. 1998)

Step 1: Relabel

Recognize the intrusive thoughts and urges as due to a medical illness called OCD.

Step 2: Reattribute

Realize that the intrusive thoughts or urges are caused by certain biochemical imbalances (reduced level of serotonin) and malfunctioning circuits in the brain. They are “false brain messages”. Remember, “It’s not me, it’s the OCD.”

Step 3: Refocus

Work around the OCD thoughts by not giving in to a compulsion.

Practice ERP daily: In ERP key to success is practicing it daily. Patients should continue with the ERP activity regularly until their anxiety or discomfort is significantly decreased.

Do not avoid doing things: Patients with OCD usually avoid anxiety provoking situations or postpone their activities, which will keep their OCD alive.

Do not substitute compulsions: By substituting one compulsion for another, the very purpose of ERP is not served, as habituation will not occur to the anxiety (Graph – 1).

Avoid using any anxiety reducing techniques: Anxiety reducing techniques come in the way of habituation. Staying with the anxiety until it reduces substantially or disappears allows habituation to occur. (Graph – 2)

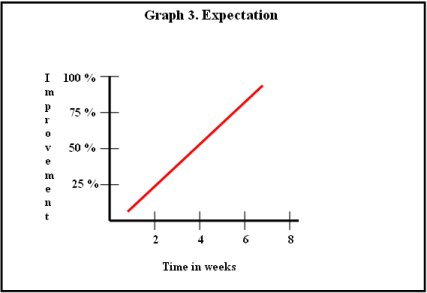

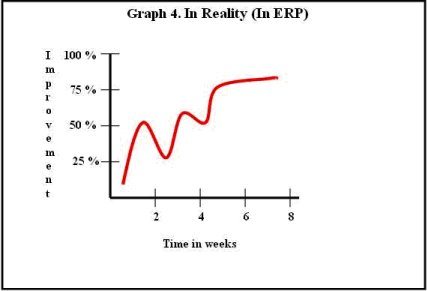

Expectation: Keep realistic expectation, unrealistic expectation will come in the way of ERP.

Step 4: Revalue

This is the natural outcome of the first three steps. Successful practice of these steps results in revaluing obsessive-compulsive behaviors as worthless distractions to be ignored.

How is CBT done at NIMHANS?

You may be advised to undergo CBT on your consultation with the doctor at the OCD clinic. Therapy may be initiated at any given time in the treatment of OCD, and this is done based on your preparedness and motivation, and the feasibility (ability to attend sessions at least once weekly). If it is feasible for yo to attend therapy on an outpatient basis at NIMHANS, you will be assigned a therapist, who would usually be a qualified or trainee psychiatrist, clinical psychologist or psychiatric social worker, all of whom are trained and supervised by the OCD Clinic Team at NIMHANS. The average number of sessions for a course of CBT for OCD is around 15 to 20, and can be taken at 1 or 2 sessions per week.

In case it is not feasible for you to come for sessions on a regular basis as an outpatient you may either be referred to a therapist close to your residence. In case there is no suitable therapist available near you, your OCD is severe and you wish to undergo therapy at NIMHANS, you may be advised admission to undergo CBT as an inpatient. You may refer to the page on “Inpatient Services” for more details on the procedure, rules, etc. for admission.

Our clinical experience suggests that the cooperation and support from the family often play a vital role in the treatment of OCD. OCD rarely leaves the family system unaffected. Marital discord, divorce and separation are common results of the stress that OCD puts on family members. Some families blame themselves for their child or spouse’s illness. Family’s sense of guilt and shame may be further reinforced by the advice from friends and relatives who often tell them that the patient is “not ill, just going through a bad phase”, and more discipline and attention is the solution to the patient’s problems. The family is often uncertain whether the rituals are part of an illness or willful behaviors for attention and control. Family responses to OCD are of three patterns: the accommodating, antagonistic and split family.

Accommodating families are usually overinvolved, permissive, and intrusive in relating to the patient. Family members often join in and help in patient’s rituals to reduce tension in the family. This is not only counterproductive for the patient but also creates tension in the family. On the other hand, antagonistic families refuse to involve themselves in patient’s problems. They are rigid, detached, hostile, critical and punitive. Anger, conflict among family members, and on occasions physical violence are common in such families. In the split family, some are overinvolved and the others are critical, hostile and uninvolved. It is clear that these three commonly seen family responses to OCD are not conducive for recovery and treatment of OCD. Hence, the involvement of family members in the treatment of OCD is necessary, particularly in the implementation of behavior therapy and monitoring of drug administration.

Patient and a family member (who can be a co-therapist in ERP) can learn about principles and techniques of ERP. Family members can assist the patient in graded exposure and response prevention. This would help outpatient ERP that can be practiced at home. Family members should be aware that unrealistic expectation (as illustrated in the Graph 3 ) might result in disillusionment and poor adherence to therapy.

Graph 3 – Expected improvement progress

On the other hand, improvement occurs in a slow fluctuating manner (as illustrated in Graph 4) and this realization would help families appreciate the gains that occur over the course of therapy.

Graph 4 – Improvement progress in reality

1. A 25-year-old housewife was brought to hospital by her husband and parents-in-law that she spends hours washing her hands. On further examination, she revealed that she feared her hands were unclean and as a result she indulged in repeated hand-washing to ensure her hands were clean. She avoided touching door handles, picking up objects on floor, old currency notes, window panes, buckets and mugs used by others. She even avoided using the same toilet used by others. Brushing her teeth would take about 30 minutes because she feared that her teeth were not clean. Because of her preoccupation with cleanliness, she would spend about 20-30 minutes washing her hands every time she touched any object or article that she thought was dirty (e.g. Door knobs, dining table, combs, soap box etc.) She would clean the bathroom, buckets, mugs and even taps and soaps for about an hour or two before she took bath and another 2 hours to bathe. Her fear that she was not completely free of dirt would drive her to apply soap repeatedly and as a result she would be extremely tired by the time she came out of the bathroom. Her life and daily activities revolved entirely around her preoccupation with cleanliness and she would be left with very little time to do anything else. Of late, her obsession with cleanliness had reached to such an extent that she would force her husband to repeatedly wash hands before he did anything. She was aware that her preoccupation with cleanliness was irrational and excessive, but nevertheless she was unable to control because of severe anxiety.

2. A 30-year-old bank employee working as a cashier suffered from a doubt that he has not counted currency notes properly before handing over the cash to customers. His doubt was that, either he had given more or less money than what was intended to be given. If more money is given, he would be held responsible and if less money is given the customer would shout at him. These incessant doubts interfered in discharging his duty as a cashier. It was particularly problematic for him in the first week of every month when a large number of customers visited his bank. He would end up counting over and over again and as a result customers would shout at him for his inefficiency and slowness. He even received memos from his bank manager for his inefficiency, and became an object of ridicule in his office, which left him feeling ashamed and depressed. Upon further questioning, he revealed that he also checks door lock of his residence at least for about 10-15 minutes before retiring to bed in the night. He even checked all the electrical appliances several times to ensure that they were switched off properly. These checking and counting rituals had become a source of great distress and anxiety to him as he was very well aware that they were clearly excessive and unnecessary.

3. A 16-year-old student was referred by a general practitioner with the complaint that he never went to school on time, because he spent more time preparing to go to school than actually going. Parents revealed that he would never be satisfied with the way his things were arranged on his reading table and the books in his school bag. He would spend about 2 hours in the morning arranging and rearranging various things related to his school and would be invariably late. If forced by his parents to hurry up, or if someone handled his personal belongings he would get extremely upset with them. Parents also reported that he spent about an hour making his bed before retiring to bed in the nights. Because of his excessive preoccupation with keeping things in an orderly fashion, he was hardly left with any time to study and complete homework and other school assignments. As a result, he went down in the ranking and teachers started complaining about his academic decline.

4. A 23-year-old agriculturist used to get repetitive images of naked women whenever he saw them. He used to get these images even upon seeing his mother, sisters, and young girls. These unwanted images would evoke intense anxiety and guilt in him. As a result he developed severe depression and suicidal ideas. He started avoiding eye contact with women, including his mother and sisters and became more and more isolated. He stopped attending social functions where he would have to invariably meet women. He also started to recite prayers in his mind to counter these images, but nude images could not be controlled. His family members brought him for treatment because of his depression and an attempt to kill himself by hanging.

5. A 26-year-old doctor developed urges to harm others. These urges caused intense anxiety and guilt because they were quite against her usual friendly nature. These urges were particularly more severe whenever she was with her 2-year-old daughter. She feared she might stab her daughter with a knife and as a result she was compelled to get rid of all the knives in her house. Her fear that she might stab her daughter became so serious that she would send her daughter to her parents’ house frequently on some or the other pretext and would not bring her back. She sought psychiatric consultation because the urges did not go away despite her efforts to control and they started interfering in her work.

6. A 20-year-old engineering student came to hospital with 2 years’ history of unwanted thoughts. He reported getting repetitive thoughts as to what will happen if his father dies, the changes that will occur in home following father’s death, changes in his financial status etc. All these related thoughts would come one after another in a sequential manner finally leading to original distressing thought of his father’s death. Patient knew that his father was doing well except for occasional pain in the abdomen and believed that these thoughts were foolish, but could not control them.

7. A 24-year-old agricultural manual labourer presented with complaints of repetitive urges to abuse elders and God with vulgar words. These urges would come upon seeing elderly people, photographs of Gods or when he walked across a temple. The urges caused intense distress in him because he was a God-fearing and religious person and respected elders. He tried to stop these urges by pressing his lips tightly as he feared he might utter obscenities but was not successful. He avoided taking to elders and visiting temples. Psychiatric consultation was sought because urges became unbearable.

8. A 27-year-old male, photographer by profession came to the hospital with 2 years’ history of getting repetitive images of day-to-day events, his interactions with other people, his girlfriend, etc. He felt that these images were not pleasurable and considered them as unwanted and intrusive. He tried to control these by telling himself not to think about them but in vain, as they used to come again and again.

9. A 22-year-old security guard presented with complaints of disturbing thoughts. He used to get repetitive thoughts about any news item which he read in the newspaper or heard over the radio. These thoughts would come to his mind repeatedly beyond a point of relevance, even though the news items were unimportant. He would try to stop these thoughts by thinking about his future and other events, but they would come back after some time.

It has often been stated that OCD is a chronic illness and that few patients recover from it. However, research by several OCD specialists suggests that this is not the case, and that a good proportion of patients with OCD recover well. Here are some of the findings of two studies done at NIMHANS to study the long-term outcome of patients being treated by us for OCD.

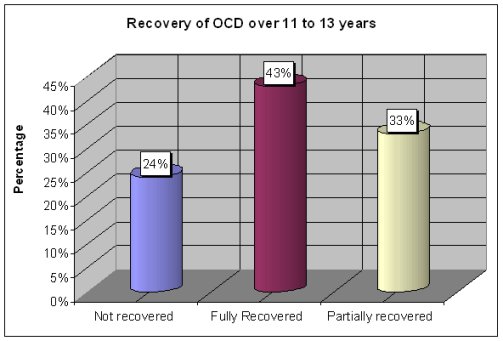

Chart 1. Recovery of OCD over 11 to 13 years

(Reddy et al., Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 2005;66:744-749)

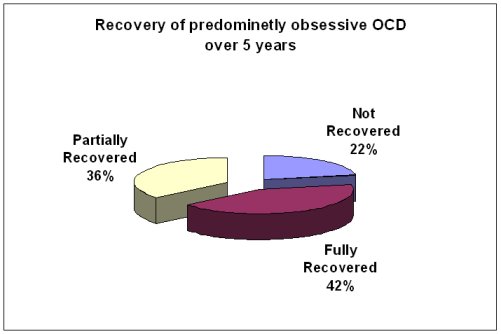

Chart 2. Recovery of predominantly obsessive OCD over 5 years

(Math et al., Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 2007;49:250-255)

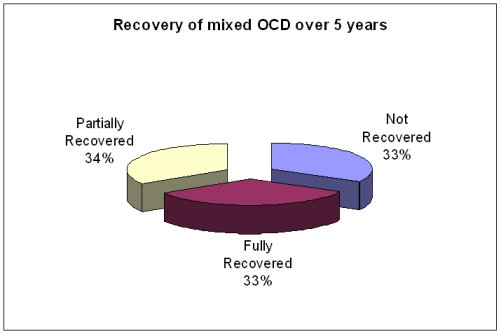

Chart 3. Recovery of mixed OCD over 5 years

(Math et al., Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 2007;49:250-255)

In the first study, 75 patients with OCD were followed up over a period of 11 to 13 years and examined, to see what had happened to their illness. It was found that 57 of them (76%) were doing well: 32 (43%) had no OCD, and a further 25 (33%) were partly recovered, meaning that their symptoms had shown a good improvement and were not interfering in their lives. Most of these patients were on treatment, but a total of 28 patients (37%) were free of OCD despite having discontinued treatment.

In the second study, patients who had only obsessions were compared with those who had both obsessions and compulsions and followed up after 5 years to know their outcome. Again, it was found that 78% of the patients with obsessions, and 66% of the patients with “mixed” OCD, were doing well. 33% of the former patients and 21% of the latter were free of OCD and not taking any medications.

Therefore, our research suggests that patients with OCD may not have such a bleak course as was once thought, and that a majority of them do well in the long run. A minority continue to do well despite not taking treatment, suggesting that such patients have truly “recovered” from the illness.

OCD was once thought to be rare in children and adolescents. This is because its manifestations in childhood may be subtle and difficult to recognize, and also because OCD symptoms may be confused with normal behaviours and superstitions that are a part of childhood, such as “lucky numbers” or bedtime rituals. However, we now know that up to half of adult OCD patients may have experienced their first symptoms in childhood and adolescents. Studies done in India as well as around the world suggest that it may affect 1-4% of children. Symptoms may begin in early childhood (around 6-7 years) or in adolescence, and are commoner in boys than in girls.

OCD is diagnosed in children using the same methods as in adults. The important differences are that:

1. Children may not find their behaviours unreasonable, whereas most adults will usually acknowledge that their symptoms are irrational.

2. Children may not be able to express the exact nature of their thoughts and fears. Sometimes, they may say that they perform compulsions until they feel “just right” or “satisfied”, rather than to diminish anxiety or distress, or describe a vague sensation that “something bad” will happen if they do not carry out their compulsive behaviours.

Common symptoms in childhood OCD are similar to those in adults, and include obsessions related to contamination, aggressive themes, a need for symmetry and exactness, and sexual and blasphemous thoughts, and compulsive washing, repeating, ordering, counting It is important to note, though, that up to one-third of children may have “miscellaneous” obsessions and compulsions that do not fit into these categories. Children often may not report these symptoms and may try to conceal them, as they find them embarrassing. Often, the first indicator of OCD may be slowness, pending excessive time in routine activities, avoiding certain situations, social withdrawal, or difficulties in academics. Children with these symptoms should be evaluated to identify OCD, as well as to differentiate it from conditions such as depression, anxiety or learning disability.

As in adults, up to two-thirds of children with OCD may suffer from additional psychiatric disorders. These include depression and anxiety disorders, as in adults. Some specific conditions that may be seen in children and adolescents include separation anxiety disorder, attention-deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), conduct disorders, tic disorders and Tourette’s syndrome.

It was previously believed that OCD in children was a severe form of the illness, and that most children did not recover. However, research done at NIMHANS and elsewhere suggests that this is not the case.

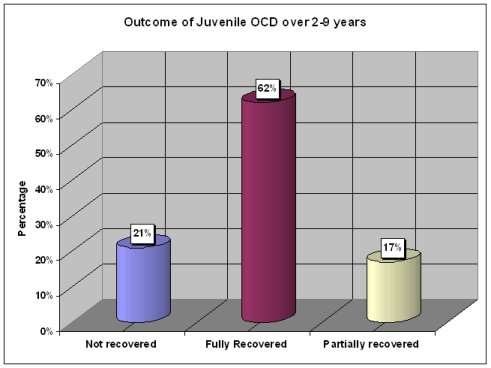

Chart – Outcome of juvenile OCD 2-9 years (Reddy et al., Acta Psych Scandi 2003;107:457-464)

Follow-up of patients with OCD in childhood up to 9 years revealed that 62% of them were free of OCD in the long run. A further 17% had mild symptoms that did not interfere in their lives, and only 21% continued to have OCD.

Treatment of childhood OCD is almost similar to adult OCD. Both medications and behavior therapy are effective.